I read this enthralling book titled ‘Invisible Cities’ written by Italo Calvino in 1972, for one of my modules a few semesters back, and it has always stuck with me. Visualising and describing elaborate cities that do not exist in reality in such an intricate manner is certainly mind-bending and fascinating.

The book is divided into 10 different sections, each consisting of groups of cities built based on a certain primary feature. Each of the 55 (unreal) cities in this book possesses a unique name — one that captures the essence of its inhabitants, its architecture, and its energy. The etymological reasoning behind the names is yet another beguiling topic I intend to cover in this blog as we explore the various cities.

I have chosen 5 of my favourite stories describing the following cities — Thekla, Aglaura, Zoe, Adelma and Leonia.

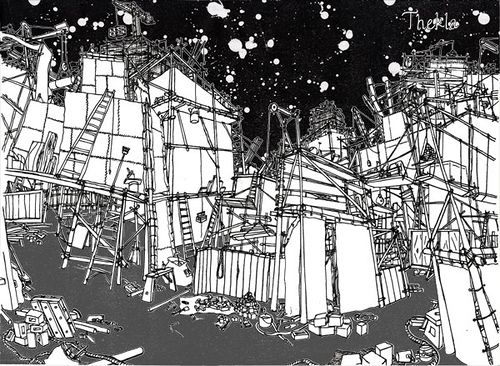

Thekla

Those who arrive at Thekla can see little of the city, beyond the plank fences, the sackcloth screens, the scaffoldings, the metal armatures, the wooden catwalks hanging from ropes or supported by sawhorses, the ladders, the trestles.

If you ask, ‘Why is Thekla’s construction taking such a long time?’ the inhabitants continue hoisting sacks, lowering leaded strings, moving long brushes up and down, as they answer, ‘So that its destruction cannot begin.’ And if asked whether they fear that, once the scaffoldings are removed, the city may begin to crumble and fall to pieces, they add hastily, in a whisper, ‘Not only the city.’

If dissatisfied with the answers, someone puts his eye to a crack in a fence, he sees cranes pulling up other cranes, scaffoldings that embrace other scaffoldings, beams that prop up other beams. ‘What meaning does your construction have?’, he asks. ‘What is the aim of a city under construction unless it is a city? Where is the plan you are following, the blueprint?’.

‘We will show it to you as soon as the working day is over; we cannot interrupt our work now,’ they answer.

Work stops at sunset. Darkness falls over the building sites. The sky is filled with stars. ‘There is the blueprint,’ they say.

What Does Thekla Symbolise?

The people of Thekla are interesting characters.

They are constantly working on their town and toil hard to accomplish a goal that is impossible to achieve — an unattainable level of perfection. Every day, they feel utter gratification from working hard due to the mere belief that one fine day, they will create the paragon of a city — an ideal, perfect Thekla.

The concept of inadequacy is frightening to Thekla’s residents. Thekla is always a work in progress, and its inhabitants dare not think of it as a flawed city, although being functional always implies imperfections. After all, even the most functional of cities have their own defects.

What does such desire for perfection say about the people of Thekla?

These people look up to the sky for inspiration; the sky is their blueprint. They tell each other, ‘Tomorrow, we will continue working on the city as the sun sets, almost as if they are saddened that work has stopped. It is as though they see no purpose in existing except to work on constructing Thekla.

We can say that these people are Thekla itself. Their identities and beings are inextricably intertwined with the city’s physical structure. If the city were to reach a completion point, they fear a loss of themselves and their essence.

For, who are they when the city has been fully constructed? What would they do with their time? Where would they go? What would they do to satisfy their calling (is there even one?)

One might read the story of Thekla and be prompted to think of its physical architecture — but this story runs even deeper. It unearths the lack of spiritual depth that the people of Thekla (and even many of us) have, which results from an overt dependence on one particular aspect of life. When we micromanage that one aspect and strive to make it perfect and flawless, satisfaction is simply out of the question.

A work that is always in progress can also never start to deteriorate. It is never exposed to the seasons and never weathers. It is stuck in a never-ending journey of getting closer to perfection and is always neither here nor there. Neither imperfect nor perfect. Neither new nor old. Neither functional nor dysfunctional.

Apart from the loss of their identity, what Thekla’s residents fear by the completion of their town, is the fate of its inevitable wizening. However, wearing out is natural for all beautiful things and fearing this often ends up in an utter refusal to let go of beloved things.

Everything has its time, and delaying it is nothing but a temporary solution.

Etymology of Thekla

Thékla is of Greek origin and means ‘God’s Fame/Glory’.

Thekla’s residents strive for perfection as they look at the sky (God’s creation) for inspiration. They wish that their town attains a magnificence that resembles that of the glorious night sky.

The glory they desire to achieve is not just for the town but also for themselves, for they are Thekla.

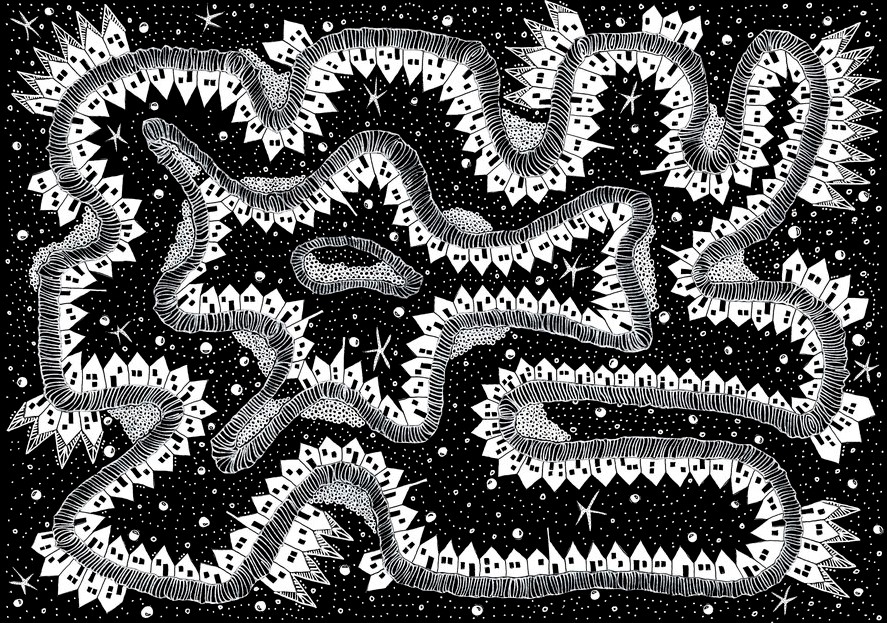

Artistic Interpretations of Thekla

AGLAURA

There is little I can tell you about Aglaura beyond the things its own inhabitants have always repeated: an array of proverbial virtues, of equally proverbial faults, a few eccentricities, some punctilious regard for rules. Ancient observers, whom there is no reason not to presume truthful, attributed to Aglaura its enduring assortment of qualities, surely comparing them to those of the other cities of their times.

Perhaps neither the Aglaura that is reported nor the Aglaura that is visible has greatly changed since then, but what was bizarre has become unusual, what seemed normal is now an oddity, and virtues and faults have lost merit or dishonour in a code of virtues and faults differently distributed.

In this sense, nothing said of Aglaura is true, and yet, these accounts create a solid and compact image of a city, whereas the haphazard opinions which might be inferred from living there have less substance. This is the result: the city that they speak of has much of what is needed to exist, whereas the city that exists on its site, exists less.

So if I wished to describe Aglaura to you, sticking to what I personally saw and experienced, I should have to tell you that it is a colourless city, without character, planted there at random. But this would not be true, either: at certain hours, in certain places along the street, you see opening before you the hint of something unmistakable, rare, perhaps magnificent, you would like to say what is it, but everything previously said of Aglaura imprisons your words and obliges you to repeat rather than say.

Therefore, the inhabitants still believe they live in an Aglaura which grows only with the name Aglaura and they do not notice the Aglaura that grow on the ground.

And even I, who would like to keep the two cities distinct in my memory, can speak only of the one, because the recollection of the other, in the lack of words to fix it, has been lost.

What Does Aglaura Symbolise?

This story about Aglaura, is not really about Aglaura.

Everything known and said about Aglaura are mere projections and assumptions made by inhabitants, observers and tourists. The story does not imply that there is nothing real in Aglaura. Instead, it reveals the ascendancy of word of mouth and how rumours about something or someone reign over facts.

Even though the original and impressive features of Aglaura are to be marvelled at, one faces a certain mental block and is unable to perceive them as genuine and authentic. It is as if they have an inner voice whispering that what they see in reality is a lie and what they think in their mind is indeed the truth. This is very natural and common for us, even in the modern era.

Possessing preconceived notions or stereotyping whilst interacting with someone is on par with what is said about Aglaura. Just like how the inhabitants of Aglaura fail to see what is before them in reality, we also fail to comprehend those we encounter when we stereotype them.

According to human psychology, we stereotype to simplify our world and defend ourselves against unknown/foreign ‘threats’. The deleterious effects of stereotyping are seen when we project an image about a particular person/group of people in our minds and then, based on that image, communicate.

Whatever we say when we have preconceived notions is biased and pernicious.

Stereotyping results in over-generalisation and erases individuality. Given that society is intricate and filled with inequalities and countless divisions, it is of utmost importance to prioritise facts over mental assumptions.

What we learn from the story of Aglaura is that even a majestic city, filled with stupendous views and monuments, can become blurred when we focus on the assumptions made about it and not its actuality.

The story’s ending is also noteworthy – whereby the author says that Aglaura exists as two separate realities in his mind, utterly distinct from each other. The dichotomy in his mind forces the author to pick one, and he believes the made-up story about Aglaura instead of the truth. He then justifies his action by quoting that the truth about Aglaura, unfortunately, has been lost. This is a crucial point to note.

Even if we want to believe the truth and not the rumours/preconceived ideas/stereotypes, we then face the question: What is the truth?

Often, this truth gets lost gradually over time. We stereotype so much that even those who get stereotyped forget who they are. Then, somehow the stereotypes become real, and we pat ourselves on the shoulder for being correct in our assumptions – ironic?

Stereotyping is forcing one to erase their individuality to fit a specific rubric, and then when they do, exclaiming, ‘There you go! I was right about you!’

It is, therefore, the most basic but vital responsibility to appreciate the individuality of people and embolden them to thrive.

Etymology of Aglaura

Aglaura is of Greek origin and means ‘simple/plain one’. In the context of this story, Aglaura might be understood as ‘straightforward’ or ‘without introspection’.

According to Greek mythology, Aglaura was the daughter of King Cecrops.

Aglaura appears in an English Renaissance play by Sir John Suckling set in Persia from 1625-1649. According to this play, both the King of Persia and his son, Prince Thersames, were in love with Aglaura. Aglaura loves Prince Thersames and marries him in secret. However, she mistakes Prince Thersames for the King and kills him. Upon realising this, she then dies as well.

The protagonist of this play is named Aglaura based on the fact that she assumes. She assumes that Prince Thersames is the King and kills him, resulting in the loss of both their lives and chance at love.

Similarly in the story above, Aglaura is a compendium of people’s assumptions.

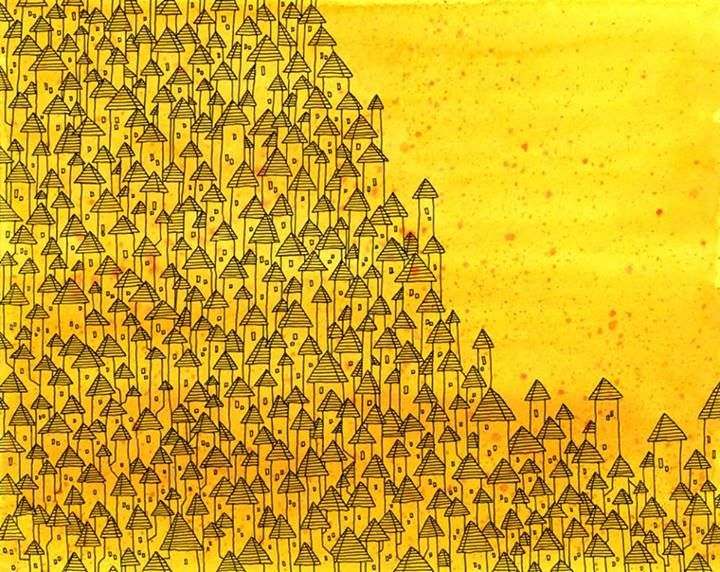

Artistic Interpretations of Aglaura

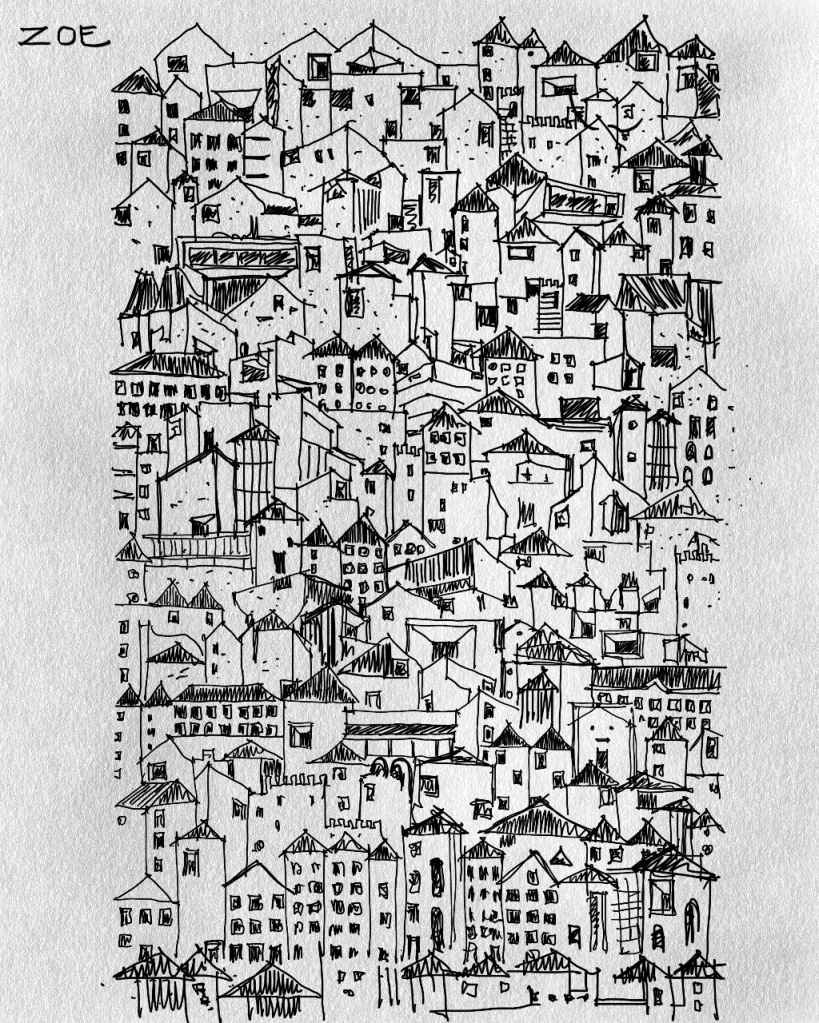

ZOE

The man who is travelling and does not yet know the city awaiting him along his route wonders what the place will be like, the barracks, the mills, the theatre, the bazaar. In every city of the empire every building is different and set in a different order: but as soon as the stranger arrives at the unknown city and his eye penetrates the pine cone of pagodas and garrets and haymows, following the scrawl of canals, gardens, rubbish heaps, he immediately distinguishes which are the princes’ palaces, the high priests’ temples, the tavern, the prison, the slum.

This — some say — confirms the hypothesis that each man bears in his mind a city made only of differences, a city without figures and without form, and the individual cities fill it up.

This is not true of Zoe.

In every point of this city you can, in turn, sleep, make tools, cook, accumulate gold, disrobe, reign, sell, question oracles. Any one of its pyramid roofs could cover the leprosarium or the odalisques’ baths. The traveller roams all around and as nothing but doubts: he is unable to distinguish the features of the city, the features he keeps distinct in his mind also mingle.

He infers this: if existence in all its moments is all of itself, Zoe is the place of indivisible existence.

But why then, does the city exist? What line separates the inside from the outside, the rumble of wheels from the howl of wolves?

What Does Zoe Symbolise?

A key phrase from this story about Zoe is ‘indivisible existence’. This means, that the city only exists because all its constituents exist. If any one constituent falls apart, the entire city falls apart.

The protagonist of the story, the traveller, enters Zoe with his own idea of what a city is made up of. Before he even enters Zoe, he predicts that he would see the typical features of a city, such as the barracks, mills, theatre, and the bazaar. However, he is surprised as he enters Zoe, for every single feature he encounters, is intricately connected to one another. The landmarks of the city are so tightly (indivisibly) connected to one another, that he literally cannot tell them apart — they look like they are one and the same, yet, exist as separate entities.

What the traveller takes some time to realise is that, upon entering the city, the traveller too, has become a part making up Zoe. His existence has now become an inseparable and non-detachable element of Zoe. He is, in a way, Zoe itself.

He thought he was entering a city, but he has unknowingly entered a dimension where he may now be even considered a feature or a ‘landmark’ defining the city.

But, what is the point of a city where nothing exists separately? Typically, a city is made up of different elements serving varying purposes – this is what allows the city to function. If A is not entirely A but a bit of B, and B is the same with C and so on … what can we say about the overall functionality of Zoe as a city?

This raises the question – Is the dependency of one aspect on another important? And if so, to what extent?

The antipathetic story of Zoe induces in the reader an aversion toward the overt interconnectivity within the city. However, as much as the story makes us uncomfortable, even the lives that you and I live are not as separate and detached as we may think (or want to think). Every single action and word of ours — the lack of it, too — has an impact. One might read the story of Zoe and loathe the suffocating situation that the inhabitants of the city are in, but it is only a matter of time before he or she realises that this is how we live too.

As a society, we are headed towards globalisation and increased connectivity. News travels around the globe in the wink of an eye, and every now and then, we feel overwhelmed – at how connected everything is.

But this is the real question: Is the feeling of being overwhelmed strong enough to stop you from being this connected with the rest of the world? If we were to take a petition to see if people would give up being so connected and updated with the rest of the world, what percentage of people do you think would actually agree to do so?

If you know the answer, then we cannot judge the inhabitants of Zoe for living in such a connected city and being content with it.

Just like the traveller, you and I are now defining features of the cities we live in.

Etymology of Zoe

Zoe is of Greek origin and means ‘life’.

In this story, the author describes Zoe as a place of ‘indivisible existence’. It is plausible that he chose this name for the city as he thought that the two definitions, ‘life’ and ‘indivisible existence’, are fitting synonyms.

Furthermore, Zoe is derived from the word ‘Eve’, which is of Latin and Hebrew origin. Eve means ‘life’ as well, and is the name of the first woman in the Bible. The idea of interconnectivity/indivisible existence is strongly attached to Eve as she was created from one of Adam’s ribs.

Artistic Interpretations of Zoe

ADELMA

Never in all my travels had I ventured as far as Adelma.

It was dusk when I landed there. On the dock the sailor who caught the rope and tied it to the bollard resembled a man who had soldiered with me and was dead. It was the hour of the wholesale fish market. An old man was loading a basket of sea urchins on a cart; I thought I recognised him; when I turned, he had disappeared down an alley, but I realised that he looked like a fisherman who, already old when I was a child, could no longer be among the living. I was upset by the sight a fever victim huddled on the ground, a blanket over his head: my father a few days before his death had yellow eyes and a growth of beard like this man. I turned my gaze aside; I no longer dared look anyone in the face.

I thought: ‘If Adelma is a city I am seeing in a dream, where you encounter only the dead, the dream frightens me. If Adelma is a real city, inhabited by living people, I need only continue looking at them and the resemblances will dissolve, alien faces will appear, bearing anguish.

In either case, it is best for me not to insist on staring at them.’

A vegetable vendor was weighing a cabbage on a scale and put it in a basket dangling on a string a girl lowered from a balcony. The girl was identical with one in my village who had gone mad for love and killed herself. The vegetable vendor raised her face: she was my grandmother.

I thought: ‘You reach a moment in life when, among the people you have known, the dead outnumber the living. And the mind refuses to accept more faces, more expressions: on every new face you encounter, it prints the old forms, for each one it finds the most suitable mask.‘

The stevedores climbed the steps in a line, bent beneath demijohns and barrels; their faces were hidden by sackcloth hoods; ‘Now they will straighten and I will recognise them,’ I thought, with impatience and fear. But I could not take my eyes off them; if I turned my gaze just a little towards the crowd that crammed those narrow streets, I was assailed by expected faces, reappearing from far away, staring at me as if demanding recognition, as if to recognise me, as if they had already recognised me.

Perhaps, for each of them, I also resembled someone who was dead. I had barely arrived at Adelma and I was already one of them, I had gone over to their side, absorbed in that kaleidoscope of eyes, wrinkles, grimaces. I thought: ‘Perhaps Adelma is the city where you arrive dying and where each finds the people he has known.

This means I, too, am dead.‘

And I also thought: ‘This means the beyond is not happy.’

What Does Adelma Symbolise?

Adelma is a city inhabited by the dead, or so most would interpret. In every face of its inhabitants, the protagonist sees someone he knows.

He recognises them as someone close to him or someone he barely knew, maybe saw them once in his lifetime. Of course, this story may be interpreted (quite directly) as the protagonist’s afterlife journey.

However, if we were to unravel the deeper meaning of the story, we may also see that it is about how haunting one’s past can be. Let’s consider two people the protagonist encounters: the old man holding the basket and the vegetable vendor. These two people resembled an old fisherman and the protagonist’s grandmother, respectively. Even though the fisherman and the protagonist’s grandmother did not negatively inflict harm on the protagonist in any overt way when he was alive, the mere memories of them are uncomfortable for the protagonist to face and relive. But why? What exactly is it about olden things or things that no longer exist that make the protagonist so uncomfortable?

The fact that they died. The fact that they are over. The fact that they will never exist for the first time again.

Even though they do not carry any negative memory with them, the finiteness of the people that the protagonist encounters in Adelma upsets him. This is something we also know and always carry with us whilst we live and breathe. The concept of ‘this will be the last time’ is something all of us have somehow internalised, and that has made us all perpetually a little sad. This sadness has actually become a part of us. The idea that all things end is neither a shock nor something we have properly learnt to live with. Unfortunately, I do not assume that there is a ‘proper’ way to learn how to process that too.

However, if we were, like the protagonist, to come directly face to face with something from our past, we would be severely devitalised, as if life has drained out of us. As the protagonist says, such an experience would be akin to a frightening dream.

To cope with this fear that he has, the protagonist then comes up with a strategy for himself to follow. He thinks to himself, ‘I need only continue looking at them, and the resemblances will dissolve, alien faces will appear, bearing anguish’. This is a real mental process, as explained by the Baader-Meinhof Phenomenon. The Baader-Meinhof Phenomenon posits that, for instance, when you start repeatedly noticing red cars around you, it is not that there are suddenly more red cars; it is just that your awareness of them has increased, and you notice them more. The red cars were always there.

The protagonist is attempting to reduce his awareness of death in the story, for the less he cares about the other characters and their death, the less they will be noteworthy to him. This is also the same mental strategy we adopt when we try to be less bothered by things that are upsetting to us, isn’t it? Even if it is not a permanent solution, for most of us, it offers temporary relief.

Many activities have been created based on this belief, such as social drinking or going to parties. These activities allow us to reduce our awareness of things that stress us and, therefore, be less bothered by them – at least temporarily.

However, the protagonist eventually realises that this strategy no longer works (like we all always do), and he starts seeing the evident reality once again that everyone around him is a dead person he once knew. He then reaches the next stage of his enlightenment, that not only are those around him dead – he is also dead. In the eyes of those around him, he, too, is a dead person from their respective past lives.

The story, therefore, takes us through the journey of the protagonist, where he confronts both his past and present. Both are equally devastating, confirmed by his final sentence that the ‘beyond is not happy’.

But was his past happy? That is and has always been a complex question.

We are all trying to answer that question.

Etymology of Adelma

Adelma is of Old German origin and means ‘noble man’.

However, Adelma might have also been derived from the Greek word Adámas, which means ‘cannot be destroyed/invincible’. In the context of this story, the Greek meaning of Adámas is more relevant.

In a way, the past life and the memories one accumulates from it cannot be ever destroyed — even after death.

Artistic Interpretations of Adelma

LEONIA

The city of Leonia refashions itself every day: every morning the people wake between fresh sheets, wash with just-unwrapped cakes of soap, wear brand-new clothing, take from the latest model refrigerator still unopened tins, listening to the last-minute jingles from the most up-to-date radio.

On the sidewalks, encased in spotless plastic bags, the remains of yesterday’s Leonia await the garbage truck. Not only squeezed tubes of toothpaste, blow-out light bulbs, newspapers, containers, wrappings, but also boilers, encyclopedias, pianos, porcelain dinner services. It is not so much by the things that each day are manufactured, sold, bought that you can measure Leonia’s opulence, but rather by the things that each day are thrown out to make room for the new. So you begin to wonder if Leonia’s true passion is really, as they say, the enjoyment of new and different things, and not, instead, the joy of expelling, discarding, cleansing itself of a recurrent impurity. The fact is that street cleaners are welcomed like angels, and their task of removing the residue of yesterday’s existence is surrounded by a respectful silence, like a ritual that inspired devotion, perhaps only because once things have been cast off nobody wants to have to think about them further.

Nobody wonders where, each day, they carry their loads of refuse.

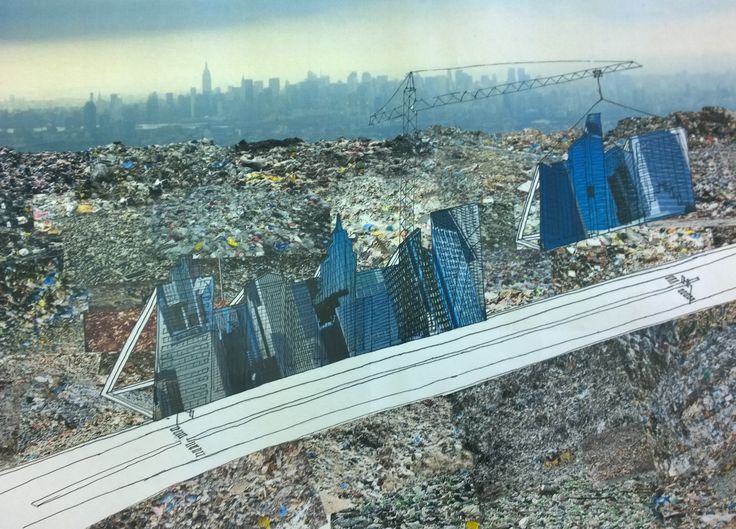

Outside the city, surely; but each year, the city expands, and the street cleaners have to fall farther back. The bulk of the outflow increases and the piles rise higher, become stratified, extend over wider perimeter. Besides, the more Leonia’s talent for making new material excels, the more rubbish improves in quality, resists time, the elements, the fermentations, combustions.

A fortress of indestructible leftovers surrounds Leonia, dominating it on every side like a chain of mountains.

This is the result: the more Leonia expels goods, the more it accumulates them; the scales of its past are soldered into a cuirass that cannot be removed. As the city is renewed each day, it preserves all of itself in its only definitive form: yesterday’s sweepings piled up on the sweepings of the day before yesterday and all of its days and years and decades.

Leonia’s rubbish little by little would invade the world, if, from beyond the final crest of its boundless rubbish heap, the street cleaners of other cities were not pressing, also pushing mountains of refuse in front of themselves. Perhaps the whole world, beyond Leonia’s boundaries, is covered by craters of rubbish, each surrounding a metropolis in constant eruption. The boundaries between the alien, hostile cities are infected ramparts where the detritus of both support each other, overlap, mingle.

The greater its height grows, the more the danger of a landslide looms: a tin can, an old tire, an unravelled wine flask, if its rolls towards Leonia, is enough to bring with it an avalanche of unmated shows, calendars of bygone years, withered flowers, submerging the city in its own past, which it had tried in vain to reject, mingling with the past of the neighbouring cities, finally clean. A cataclysm will flatten the sordid mountain range, cancelling every trace of the metropolis always dressed in new clothes.

In the nearby cities they are all ready waiting with bulldozers to flatten the terrain, to push into the new territory, expand, and drive the new street cleaners still farther out.

What Does Leonia Symbolise?

Leonia not only symbolises an environmental nightmare but the naivety (or stupidity) of the inhabitants of the city.

In Leonia, the currency is not money but the amount of rubbish one can generate.

The more trash you accumulate, the richer you are. Inhabitants of Leonia indirectly compete with one another to show their affluence daily. They stand outside their houses as the cleaners arrive to boast their richness to their neighbours. They (truly) live every day as if it were their last, with no regard for the footprint they leave on their environment.

They also live in a state of complete ignorance. Once they leave their prized plastic garbage bags outside, what happens with the bags is no longer their concern. They feel less burdened and are once again free to consume, waste and not care — an unending loop. Even the mere five minutes of waiting time when they are left alone with their trash before the cleaners arrive cause the inhabitants of Leonia great discomfort. Their pride prevents them from accepting that their strive to appear richer is no longer just a game and, at this point, is simply an obstinate denial of the truth.

Without being aware of the impact of their actions, Leonia’s inhabitants continue to produce materials that ‘look and feel’ better, although that always comes at the cost of the environment. Such items are not bio-degradable, cannot be combusted, and stay the same picture-perfect way for decades. All this, for mere one-day use – utter idiocy.

The story also emphasises the role of the cleaners of Leonia and the predicament they face. The cleaners have run out of space and push the rubbish towards the mountains, eventually reaching other cities’ physical space. Somehow other cities are also facing a similar situation, and the trash from all these cities exists as one entire mass of ‘ugliness’ that all these cities are desperately trying to hide from sight.

The irony lies in how Leonia’s inhabitants wish to keep themselves, their food and their own houses clean within the city. They use fresh soap bars, consume fresh fruits, and wrap themselves with clean clothing. Leonia is constantly evolving, becoming better than yesterday. Cleaner, more modern, more technologically advanced. However, their need for hygiene only extends till the borders of their city.

Leonia stands in stark contrast to the mountains of trash just beyond the city’s border. If one were to stand at the highest point of Leonia and crane their neck, it is possible that they could see the garbage at just a mile’s distance. However, the residents of Leonia would do anything but confront the consequences of their actions. To them, their competition to live wealthier and undying pride are more important than what tomorrow may bring.

All it takes is a tin can to roll down, and that would mark the end of Leonia.

Somehow, Leonia’s residents seem to be quietly aware of this and still feel no urge to let go of their pride and accept the urgency of their situation. There is no better way to justify their lack of effort except that they have entirely given up and are simply willing to accept whatever impending doom is about to befall them. Till then (when something eventually ends their lives), they would rather continue living the way they do and prefer not to prepare for what is to come.

This story was written in 1972, but its relevance to our world today can neither be questioned nor refuted.

Etymology of Leonia

Leonia is of Greek origin and is derived from the root word Leōn, which means ‘lion’.

The lion is known for its pride, and the striking characteristic of Leonia’s inhabitants is their love for wealth, outward appearance, and status. They hold their noses up to the sky, stubbornly refusing to see their city for what it is, and this could possibly explain its naming.

Artistic Interpretations of Leonia

Leave a comment